- Introduction to our Maze Solver

- Getting Started

- Breadth First Search

- Depth First Search & Cycle Check (recommended, but optional)

- E. A* (optional)

- TA Overview

- Submission

Introduction to our Maze Solver

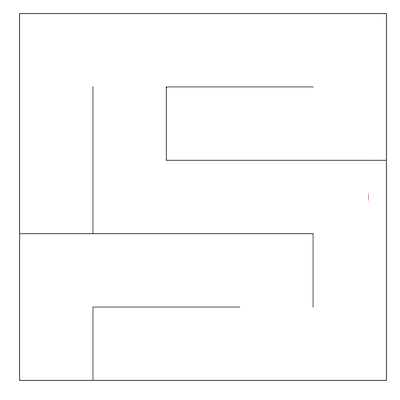

In this lab, we’ll explore how a few graph algorithms behave in the context of mazes, like the one shown below.

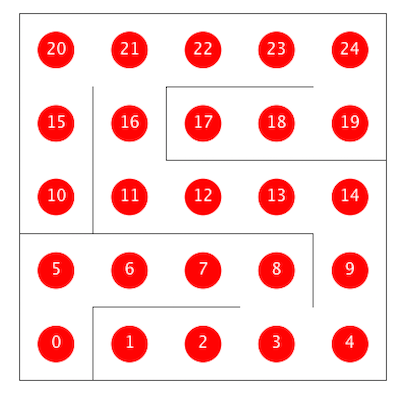

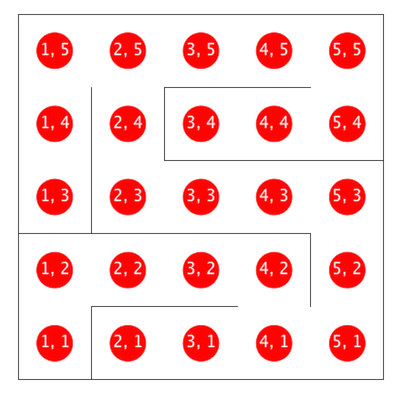

One way to represent a maze is as an undirected graph. The vertices of such a graph are shown below, with one dimensional (vertex number) coordinates shown on the top version and (X, Y) coordinates on the bottom version. If there is no wall between two adjacent vertices, then the corresponding graph has an undirected edge between the vertices. For example, adj(11) would be an iterable containing the integers 12 and 16.

In this lab, you’ll implement a few key graph algorithms using the provided Maze class, which has the following methods of interest:

public int N(): Size of the maze (mazes are N x N)

public int V(): Total number of vertices in the maze

public Iterable<Integer> adj(int v): Returns the neighbors of v

public int toX(int v): Returns the x coordinate of vertex v

public int toY(int v): Returns the y coordinate of vertex v

public int xyTo1D(int x, int y): Returns the vertex number of x, y

In this lab, you’ll consider the following five maze traversal classes:

-

TrivialMazeExplorer.java: Iterates over all spaces in the maze, marking and assigning dummy values fordistTofor all spaces (already done for you). -

MazeDepthFirstPaths.java: Uses DFS to find a path from a given source to a target vertex, terminating when the target is found (already done for you). -

MazeBreadthFirstPaths.java: Uses BFS to find a path from a given source to a target vertex, terminating when the target is found (required). -

MazeCycles.java: Searches for cycles in the maze. If a cycle is detected, the algorithm terminates (optional). -

MazeAStarPath.java: Uses A* to find a path from a given source to a target vertex, terminating when the target is found (optional).

These maze solvers should be subclasses of the abstract MazeExplorer class, which has the following fields and methods:

public boolean[] marked: Locations to mark in blue

public int[] distTo: Distances to draw over the Maze

public int[] edgeTo: Edges to draw on Maze

public Maze maze: The maze being solved

public void announce(): Call whenever you want the drawing updated

public solve(): Solves the given Maze problem

The Maze class has special functionality built in so that it can see your MazeExplorer’s public variables. Specifically, whenever you call announce, it will draw the contents of your MazeExplorer’s marked, distTo, and edgeTo arrays. Make sure to call the announce method any time you want the drawing to be updated.

Getting Started

If you’d like, watch this optional video showcasing the expected behavior of each class.

As an hands-on example, try compiling and running TrivialMazeExplorerDemo.java. Look at the TrivialMazeExplorer.java and TrivialMazeExplorerDemo.java files to understand what’s going on.

Next, as a more complex example, try running DepthFirstDemo. You’ll see that DFS runs and finds the target. This code was adapted from the DepthFirstPaths class from our optional textbook.

If you want to tweak the parameters of the maze, you can edit the maze.config file. There are three different types of mazes (SINGLE_GAP, POPEN_SOLVABLE, and BLANK) to choose from. A % sign at the beginning of a line in the config file comments it out. Feel free to play around with all different types by changing which MazeTypes are commented out.

Breadth First Search

BFS and DFS are very similar. BFS uses a queue (First In First Out, a.k.a. FIFO) to store the fringe, whereas DFS uses a stack (First In Last Out, a.k.a. FILO). Naturally, programmers often use recursion for DFS, since we can take advantage of and use the implicit recursive call stack as our fringe. For BFS, there is no implicit data structures that we can use. We must instead use an explicit data structure, i.e. some sort of instance of a queue.

Rather than writing your own, Java already has a Queue interface (a sub-interface of the almighty Collection interface) built in. Read the interface documentation carefully. Hint: see if you can see any familiar Collection-implementing class that also implements this Queue interface. Feel free to use any of them.

Write a class MazeBreadthFirstPaths.java that extends MazeExplorer. It is highly recommended you look at the code in MazeDepthFirstPaths and use it as inspiration. When you compile and run BreadthFirstDemo.java, you should see your algorithm crawl the graph, locating the shortest path from position (1, 1) to (N, N), stopping as soon as the (N, N) position is found.

You can also use BreadthFirstPaths as inspiration,

Depth First Search & Cycle Check (recommended, but optional)

In the world of graph theory, there exist many cycle detection algorithms. For example, a weighted-quick union object (without path compression) can be used to detect cycles in O(E * logV) time. For today’s exercise, we will use DFS to detect cycles in this maze (an undirected graph) in O(V + E). The idea is relatively simple: For every visited vertex v, if there is an adjacent u such that u is already visited and u is not parent of v, then there is a cycle in graph.

For this part of the lab, you’ll write a cycle detection algorithm. When you compile and run CylesDemo, you should see your algorithm crawl the graph. If it identifies any cycles, it should connect the vertices of the cycle using purple lines (by setting values in the edgeTo array and calling announce()) and terminating immediately. All visited vertices should marked, but there should be no edges connecting the part of the graph that doesn’t contain a cycle. Instead, the only edges that should be drawn are the ones connecting the cycle.

Recall from last section, you can use either recursion or a Stack class for DFS. If you decide to go with latter, we recommend using the Princeton standard libary’s Stack class rather than java.util.Stack, which has some fundamental flaws. Alternaetly, you can instead use some linear structure in a FILO fashion.

E. A* (optional)

Earlier, you created the MazeBreathFirstPaths class to find the shortest path from the source to the target.

We’ve discussed other algorithms for finding shortest paths, specifically Dijkstra’s algorithm and A*. For this lab, Dijkstra’s algorithm would behave exactly the same as MazeBreathFirstPaths (B level question: figure out why), so it’s not particularly interesting.

However, A* does give us one way to potentially improve upon the performance of BFS.

In lecture, I briefly mentioned this nice visualization for BFS, DFS, Dijkstra’s algorithm, and A* algorithm. We highly recommend playing around with it to improve your understanding of these most basic graph algorithms.

For this final and optional part of the lab, you’ll implement the A* algorithm. After completion, when you compile and run AStarDemo, you should see your algorithm crawl the graph, seeking the shortest path from (1, 1) to (N, N). Unlike BFS, the algorithm should take into account the target vertex, reducing the number of vertices that must be analyzed, while still ensuring that we find the shortest path.

For your heuristic h(v), we recommend that you use the Manhattan distance, which can be simply expressed as:

Math.abs(sourceX - targetX) + Math.abs(sourceY - targetY);

If you have time, Experiment with different graph types and heuristics to see how they behave.

Note: In HW4, you’ve already implemented A*, but that was on an implicit graph object rather than an explicit one. You’ll also implement A* in project 3, and it’s a major focus of the first two weeks of CS188.

TA Overview

At the end of lab, your TA will go over our solutions for MazeBreadthFirstPaths and MazeCycles.

Submission

You only need to submit MazeBreadthFirstPaths.java. Make sure to run BreadthFirstDemo.java and make sure that your code functions correctly before you submit!